Evaluating powered land for development involves understanding its energy infrastructure, geographic suitability, and regulatory requirements. Powered land refers to sites already assessed for energy projects, such as data centres or renewable energy facilities, due to their proximity to substations and the grid. Here's what you need to know:

- Key Factors: Assess grid capacity, geographic conditions, and environmental risks. For example, solar plants need 5–7 acres per megawatt, and substations in Dubai require specific plot sizes (e.g., 200m x 200m for 400/132kV).

- Energy Demand: Electricity needs are rising globally. The UK anticipates demand doubling by 2050, while Dubai enforces strict energy safety regulations, like backup generators for major developments.

- Regulatory Insights: Adhering to local regulations, such as Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) guidelines or the UK's National Policy Statements, ensures smoother project approvals.

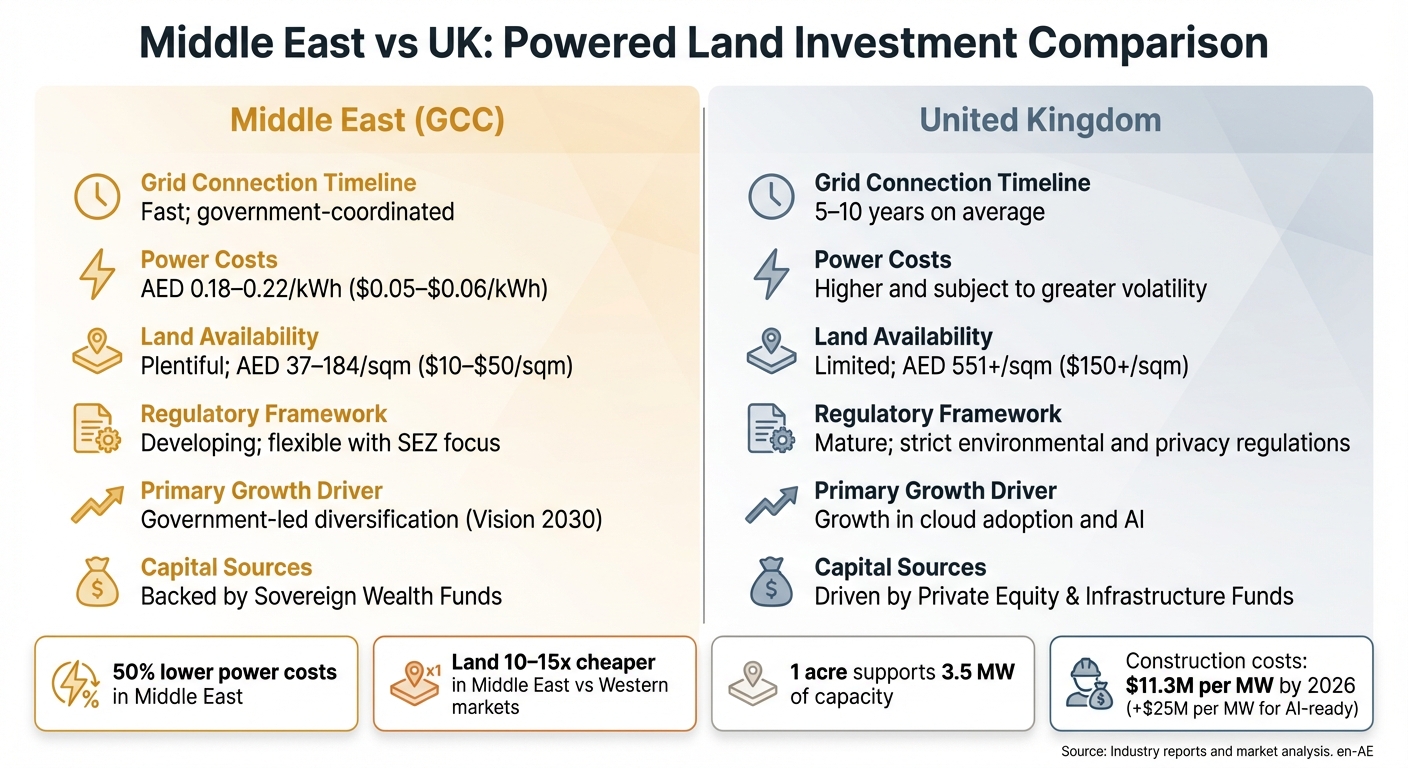

- Investment Metrics: The Middle East offers lower power costs (AED 0.18–0.22/kWh) and cheaper land (AED 37–184/sqm) compared to the UK, where land is pricier (AED 551+/sqm) and power costs are higher.

Evaluating Land Suitability and Environmental Factors

Geographic and Topographic Factors

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) play a vital role in creating detailed suitability maps. By integrating data on topography, geology, climate, and infrastructure, GIS provides a comprehensive view of potential sites. Remote sensing complements this by identifying key features such as land cover, vegetation density, and surface temperatures.

For example, in Dubai, a 400/132kV substation requires a plot measuring 200m x 200m, ideally located near high-voltage lines and fibre optic networks. In contrast, in the UK, factors like high-speed connectivity and proximity to Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are critical for optimising data centre performance.

Advanced tools like PVcase Prospect are also instrumental. This platform evaluates slopes and terrain to pinpoint buildable zones and now includes flood risk data for all U.S. counties, even those outside the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) coverage. While these technologies are powerful, they have limitations. Ground-truthing remains essential for verifying geological conditions, soil composition, and ecological factors that remote tools might overlook. These insights form the foundation for further assessments, including environmental and regulatory compliance.

Environmental Factors and Regulatory Requirements

After determining land suitability, environmental compliance becomes a critical step in assessing project feasibility. For instance, in the UK, non-fossil fuel electricity generation projects can be classified as Critical National Priority infrastructure if developers adhere to the mitigation hierarchy. This approach requires demonstrating efforts to avoid, reduce, mitigate, or compensate for significant environmental impacts.

Specific assessments are often mandatory for renewable energy projects. Solar developments, for example, must evaluate glint and glare, electromagnetic fields (EMF) for cables exceeding 132kV, and the effects of lighting on local wildlife, such as bats. GIS-based viewshed analyses and predictive modelling can address these concerns early on, guiding decisions on panel orientation and placement.

Climate resilience is another key consideration. Biomass and energy-from-waste (EfW) plants must demonstrate their ability to withstand flooding and drought, while onshore wind projects need to account for the potential increase in storm intensity. In England, EfW projects face additional requirements, such as ensuring that residual waste does not exceed 287 kilograms per person by the end of 2042.

Regulatory differences between England and Wales further complicate planning. In England, new EfW projects can proceed if they meet specific diversion and efficiency criteria. Meanwhile, Wales has implemented a moratorium on new EfW plants exceeding 10MW. Early engagement with regulatory bodies, such as the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) or Natural Resources Wales (NRW), during the pre-application phase can help align projects with Marine Licence requirements.

To ensure all environmental management measures are accounted for, maintaining a Commitments Register is essential. This document helps secure these measures within the Development Consent Order (DCO). By integrating land and environmental assessments, developers can make informed decisions and accurately evaluate the investment potential of their projects.

sbb-itb-0a9f22b

Evaluating Energy Infrastructure Availability

Grid Capacity and Renewable Energy Potential

Understanding grid capacity is crucial when assessing a site's ability to connect to the power network. In the UK, electricity demand is expected to more than double by 2050, which will require a fourfold increase in low-carbon energy generation. This projection underscores both the opportunities and challenges in meeting future energy needs.

The Renewable Energy Planning Database (REPD) offers quarterly updates on all UK renewable electricity projects exceeding 150 kW. Its interactive map provides a detailed view of the geographical distribution and development status of these projects. By identifying clusters of large-scale renewable projects through the REPD, developers can anticipate potential grid capacity limitations and the costs of necessary upgrades.

In Dubai, developers must submit a Power Supply Master Plan to DEWA, outlining load projections, phased development timelines, and technical specifications like Total Connected Load (TCL) and Maximum Demand (MD), with a minimum power factor of 0.95. For integrating renewable energy, DEWA mandates a Distributed Renewable Resources Generation (DRRG) plan for rooftop solar installations. This plan must include the intended capacity (kW) and commissioning dates.

To estimate renewable energy potential, datasets from the Global Atlas for Renewable Energy by IRENA, along with tools like the Bioenergy and SolarCity simulators, can be invaluable for analysing solar and wind capabilities across regions like the Middle East and the UK. However, even the best renewable potential is meaningless without adequate grid capacity to handle the generated power.

This naturally brings us to the importance of evaluating proximity to critical substations and transmission lines.

Proximity to Substations and Transmission Lines

The location of a project relative to existing infrastructure can directly influence both costs and feasibility. In Dubai, DEWA specifies that a standard 400/132 kV substation requires a plot size of 200 metres by 200 metres, while a 132/11 kV substation needs 50 metres by 60 metres. These substations must allow access for heavy vehicles; for instance, a 132/11 kV substation should be accessible via two major roads or one major road and a Sikka at least 7 metres wide.

Corridor requirements also play a significant role. DEWA mandates a 50-metre-wide corridor for 400 kV double-circuit tower lines and a 2.5-metre-wide corridor for each 132 kV underground cable circuit. Additionally, a 132/11 kV substation can handle up to 80 outgoing 11 kV cables, with clearances of 1 to 3 metres required from nearby pressure pipelines, depending on the pipeline's diameter.

Project timelines are another critical factor. DEWA requires advance notice for constructing or upgrading infrastructure, such as 400/132 kV and 132/11 kV substations, as well as for arranging 132 kV cables once load requirements are finalised. To ensure efficiency, developers should align their power demand phases with DEWA's commissioning schedule and strategically position 132/11 kV substations near high-demand facilities like District Cooling Plants.

Here’s a summary of DEWA’s key infrastructure requirements:

| Infrastructure Type | Required Plot Size / Corridor Width | Key Technical Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 400/132 kV Substation | 200m × 200m | Must allow access for heavy vehicles and accommodate 400 kV lines |

| 132/11 kV Substation | 50m × 60m | Should be located at the load centre with access from two major roads or one + Sikka (min. 7m) |

| 400 kV Overhead Line Corridor | 50m width | Required for double-circuit tower lines |

| 132 kV Underground Cable | 2.5m width per circuit | Must maintain a 2m minimum gap from permanent structures |

(Source: DEWA)

In the UK, climate resilience is a critical consideration for energy infrastructure. Land-based assets, such as cabling and onshore substations, must be designed to withstand risks like flooding, storm surges, and coastal erosion. Early collaboration with regulators - including the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) in England and Natural Resources Wales (NRW) - is essential during the pre-application phase to ensure infrastructure designs meet licensing and resilience requirements.

How to Assess Your Industrial Sites for Data Center Development

Understanding Regulatory and Planning Requirements

Once physical infrastructure and environmental factors are assessed, the next critical step is aligning with regulatory and planning requirements.

UAE and UK Regulatory Frameworks

The rules governing land development vary significantly between the UAE and the UK, shaping how investments are planned and executed. In Dubai, the Dubai Land Department (DLD) and the Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) oversee key aspects like project registration, developer licensing, and escrow account protection for off-plan developments.

In the UK, large-scale projects - like renewable energy installations exceeding 50 MW for biomass and waste or 100 MW for solar and offshore wind - are classified as Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs). These projects are guided by National Policy Statements under the Planning Act 2008. A revised EN-3 policy statement, which focuses on renewable energy infrastructure, will take effect from 6 January 2026. This framework prioritises non-fossil fuel electricity generation as Critical National Priority (CNP) infrastructure, balancing environmental concerns with public benefits. Such distinctions also influence taxation and land tenure rules.

"Understanding the real estate regulatory landscape is no longer optional - it's your competitive advantage."

– Saleem Karsaz, Real Estate Industry Leader

From a taxation perspective, the UAE imposes a 9% federal corporate tax on income above AED 375,000, while the UK applies a 25% standard rate. In 2025, the UK introduced major tax reforms, including the removal of the remittance basis for non-domiciled individuals and a proposed 20% exit tax on unrealised gains for high-net-worth individuals leaving the country. Both nations rely on a Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP) under their double tax treaty to resolve cross-border taxation issues, with updated guidance released by the UAE Ministry of Finance in June 2025.

| Feature | UAE (Dubai) | United Kingdom |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Regulator | DLD / RERA | Local Planning Authorities / Planning Inspectorate |

| Corporate Tax | 9% (above AED 375,000) | 25% (standard) |

| Capital Gains Tax | 0% | 10% – 28% |

| Land Tenure | Freehold (Zones) / Leasehold | Freehold / Leasehold / Commonhold |

Land Administration and Permit Requirements

Beyond regulatory frameworks, understanding local land tenure and permit processes is essential for project success. In the UAE, full foreign ownership is restricted to designated freehold zones; outside these zones, only leasehold arrangements are permitted. Developers must confirm whether land falls within these freehold areas to secure full ownership rights. Additionally, Dubai imposes a 4% one-time transfer fee through the DLD for property transactions.

For renewable energy projects, UAE law requires developers to obtain approval from the Competent Authority and sign a connection agreement with the service provider before linking renewable units to the electrical grid. Developers must also secure a specific licence for electricity production and ensure buildings are licensed for such activities. Starting 15 January 2026, all contractors in Dubai, including those operating in free zones, must be registered and classified by the Municipality. Non-compliance could result in fines of up to AED 2,000,000 for repeat offences.

In the UK, the permitting process is structured and time-bound. For Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) under TEN-E Regulations, the entire process is capped at 3.5 years, including a 2-year pre-application phase and a 1.5-year determination period. Projects below the NSIP thresholds fall under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, with Local Planning Authorities serving as the primary decision-makers. Overseas investors must also obtain an Overseas Entity ID (OE ID) from Companies House before registering freehold or long-leasehold interests with HM Land Registry. Applications without a valid ID are automatically rejected.

"The UK-UAE double tax agreement can significantly reduce or eliminate cross-border tax liabilities – but only if applied correctly."

– James Ferguson, Private Wealth Director, Titan Wealth International

For offshore projects in the UK, developers must secure leases from The Crown Estate (for England, Wales, and Northern Ireland) or Crown Estate Scotland to place structures or cables on the seabed. Early collaboration with regulators such as the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) in England or Natural Resources Wales (NRW) is crucial to align Marine Licences with the Development Consent Order (DCO) process.

These regulatory and administrative details directly affect project costs and long-term returns, making them a key consideration for investors and developers alike.

Assessing Investment Potential

Middle East vs UK Powered Land Investment Comparison: Key Metrics for Data Centre Development

Exploring powered land opportunities can reveal promising returns, but the investment dynamics for data centres and renewable energy projects vary significantly between the Middle East and the UK. These differences stem from factors like grid access, power costs, and land availability.

Speed to power is critical. In the UK, securing grid connections is notoriously slow, making existing utility commitments more valuable than even prime locations. In contrast, Middle Eastern governments streamline power and data centre planning, enabling faster deployment. The main challenge lies in securing megawatts of power, not just completing construction.

On average, one acre of land can support 3.5 MW of capacity. Construction costs are projected to hit $11.3 million per MW by 2026, with an additional $25 million per MW for AI-ready setups. In EMEA, projects using private wire transmission combined with renewable energy can cut tenant power costs by up to 40% compared to standard grid rates. These factors highlight the importance of comparing regional speed-to-power capabilities and overall cost structures.

Middle East vs UK: Investment Comparison

Here’s a look at how the two regions stack up on key investment metrics:

Key Investment Factors: Middle East vs UK

| Factor | Middle East (GCC) | United Kingdom |

|---|---|---|

| Grid Connection Timeline | Fast; government-coordinated | 5–10 years on average |

| Power Costs | AED 0.18–0.22/kWh ($0.05–$0.06/kWh) | Higher and subject to greater volatility |

| Land Availability | Plentiful; AED 37–184/sqm ($10–$50/sqm) | Limited; AED 551+/sqm ($150+/sqm) |

| Regulatory Framework | Developing; flexible with SEZ focus | Mature; strict environmental and privacy regulations |

| Primary Growth Driver | Government-led diversification (Vision 2030) | Growth in cloud adoption and AI |

| Capital Sources | Backed by Sovereign Wealth Funds | Driven by Private Equity & Infrastructure Funds |

The Middle East stands out with 50% lower power costs and land that is 10–15 times cheaper compared to major Western markets. On the other hand, the UK offers a well-established regulatory framework and a mature market infrastructure. Investors must carefully balance cost savings against the complexity of regulations when deciding between these regions.

Gamcap's Investment Approach

Gamcap’s strategy is shaped by these regional dynamics. They focus on three main approaches: in-house development from the ground up, mergers and acquisitions of assets at different stages, and joint ventures with local partners for co-development or portfolio acquisition. With over 2 GW in the pipeline and more than 100 completed projects, Gamcap targets areas like renewables, digital infrastructure, grid support, and specialised opportunities in both the Middle East and the UK.

Their approach prioritises horizontal development - securing land, entitlements, and power agreements - before committing to vertical construction. This aligns with the growing trend of treating powered land as its own asset class. By locking in megawatts early and integrating renewable energy to meet hyperscaler carbon reduction goals, Gamcap positions its projects to command a premium in markets where energy-ready sites are in short supply.

Using Decision Frameworks and Tools

Evaluating powered land requires more than just intuition - it calls for a well-structured approach supported by advanced tools. As of 6 January 2026, the updated National Policy Statements EN-1 (Overarching Energy) and EN-3 (Renewable Energy Infrastructure) have placed low-carbon infrastructure under the Critical National Priority category.

Decision-Making Models and Analysis Tools

Decision-making in this space increasingly relies on technical models like Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). These tools are invaluable for suitability mapping, as they analyse geographic and environmental data to provide actionable insights. By assessing factors such as topography, proximity to the grid, and environmental limitations, these models help pinpoint the best land parcels for development.

GIS-based viewshed analyses are another essential tool. They evaluate the extent of glint and glare from solar panels that might affect sensitive receptors, such as airports or public rights of way. Predictive modelling also plays a key role, mapping ecological receptors like bat populations alongside human receptors to guide decisions on lighting and infrastructure placement. A Commitments Register is used to track technical assumptions and mitigation measures from the early scoping stage through to the final application, ensuring consistency and facilitating a smoother regulatory review. Together, these techniques form the backbone of a systematic site selection process.

The process itself typically unfolds in four stages: identifying potential sites, assessing their suitability, drafting allocations, and confirming final selections based on data-driven evidence. For projects in England that exceed 100 MW, the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP) regime applies. This means evaluations are overseen by the Secretary of State rather than local planning authorities.

Integrating Sustainability into Development

Beyond technical evaluations, integrating sustainability considerations is essential for refining project feasibility. This process often begins with early-stage climate resilience testing. For coastal sites, this means assessing risks like storm surges and rising sea levels. Inland facilities, such as biomass or Energy from Waste (EfW) plants, are evaluated for potential drought impacts on river flows. Additionally, multi-modal transport modelling is employed to explore whether fuel and residues can be transported efficiently by water or rail instead of relying solely on road transport. This step is critical for reducing carbon emissions.

Gamcap serves as a leading example of applying these frameworks to powered land development. Their approach focuses on horizontal development - securing land, obtaining necessary entitlements, and finalising power agreements - before moving on to vertical construction. By locking in megawatts early and incorporating renewable energy solutions, Gamcap ensures its projects are robust and attractive to investors, particularly in markets where energy-ready sites are scarce.

Conclusion

Assessing powered land development opportunities calls for a methodical, data-focused strategy that takes into account factors like suitability, infrastructure, regulations, and investment potential. Whether you're analysing locations in the UAE or the UK, the core principles stay the same: secure resource availability, ensure grid compatibility, navigate intricate planning systems, and prioritise climate resilience from the beginning.

Regional frameworks further shape these evaluations. For instance, the UK's classification of renewable energy infrastructure as Critical National Priority infrastructure starting 6 January 2026 highlights the urgency of such assessments. With increasing electricity demand and stricter net-zero targets, adhering to utility-specific standards - such as DEWA's Major Project Guidelines in Dubai - ensures compliance with local grid requirements and sustainability benchmarks.

Technical precision plays a key role, as evidenced by advanced GIS tools and predictive modelling techniques. These technologies, from GIS-based viewshed analyses to predictive models for environmental and human impacts, help pinpoint the most suitable sites while addressing regulatory and environmental challenges. Tools like a Commitments Register ensure that mitigation measures are tracked consistently from the early scoping stages to final applications. Engaging with stakeholders, including regulators and local communities, early in the process can help avoid delays and secure the necessary social licence for long-term project success.

Gamcap's methodology offers a practical example of this structured approach. Their focus on horizontal development - securing land, obtaining permits, and finalising power agreements - before moving into vertical construction illustrates how prioritising foundational elements creates energy-ready sites that attract institutional investors. With over 2 GW in their development pipeline and more than 100 projects delivered worldwide, Gamcap showcases how a well-structured evaluation and strategic execution can lead to sustainable and profitable results in both emerging and mature markets.

Ultimately, success in powered land development comes down to balancing technical feasibility, financial considerations, and regulatory insight. A disciplined approach not only reduces risk but also accelerates project timelines, maximises value, and ensures readiness to meet the growing infrastructure needs of a decarbonising world.

FAQs

What are the main regulatory differences between land development in the UAE and the UK?

The legal and regulatory landscapes for land development in the UAE and the UK differ significantly, reflecting their unique systems and priorities. In the UAE, foreign investors are restricted to designated freehold zones, such as Sobha Hartland and Meydan City, where they can purchase land outright. Outside these areas, land ownership is limited to long-term leases, and investors must secure approvals from the relevant emirate authority. In contrast, the UK offers more flexibility, allowing both residents and non-residents to acquire land on either a freehold or leasehold basis. Leaseholds in the UK typically span 99–125 years and often come with additional costs like ground rent and service charges.

Taxation policies also highlight key differences. The UK imposes several taxes on land transactions, including stamp duty, council tax, and capital gains tax. On the other hand, the UAE provides a tax-free environment for income and capital gains. However, UAE investors should be mindful of registration fees and, in leasehold zones, recurring ground rent payments.

When it comes to environmental and planning approvals, the processes diverge further. In the UK, renewable energy projects must comply with the National Policy Statement EN-3, which involves a Development Consent Order (DCO) process and rigorous sustainability assessments. In Dubai, an Environmental Clearance (EC) is required, and certain projects must undergo an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), overseen by the Dubai Municipality. These procedural differences impact project timelines, required documentation, and the involvement of stakeholders in each country.

How can Geographic Information Systems (GIS) help identify suitable land for development projects?

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) serve as essential tools for developers, enabling them to evaluate land suitability by analysing various factors within a unified platform. By layering spatial data such as topography, energy infrastructure networks, protected areas, population density, and resource quality, GIS offers a comprehensive view of both opportunities and limitations for development.

This capability allows developers to swiftly pinpoint and assess land parcels that align with specific project requirements, whether for data centres or large-scale renewable energy initiatives. The result? Smarter, more strategic decisions tailored to the unique demands of the UAE and its neighbouring regions.

Why is grid capacity important for evaluating powered land development projects?

Grid capacity plays a crucial role in land development projects, especially when it comes to supporting the high, consistent power needs of data centres or large-scale renewable energy installations. If the grid can't handle these demands, projects could run into delays, higher expenses, or even risk becoming non-viable.

In regions like the UAE and the UK, where energy infrastructure and regulations differ significantly, conducting an early assessment of grid capacity is essential. This process helps reduce investment risks and ensures the site can meet the project's power requirements. Key considerations include the availability of megawatt-scale power, the potential need for infrastructure upgrades, and the long-term reliability of the grid to sustain operations.