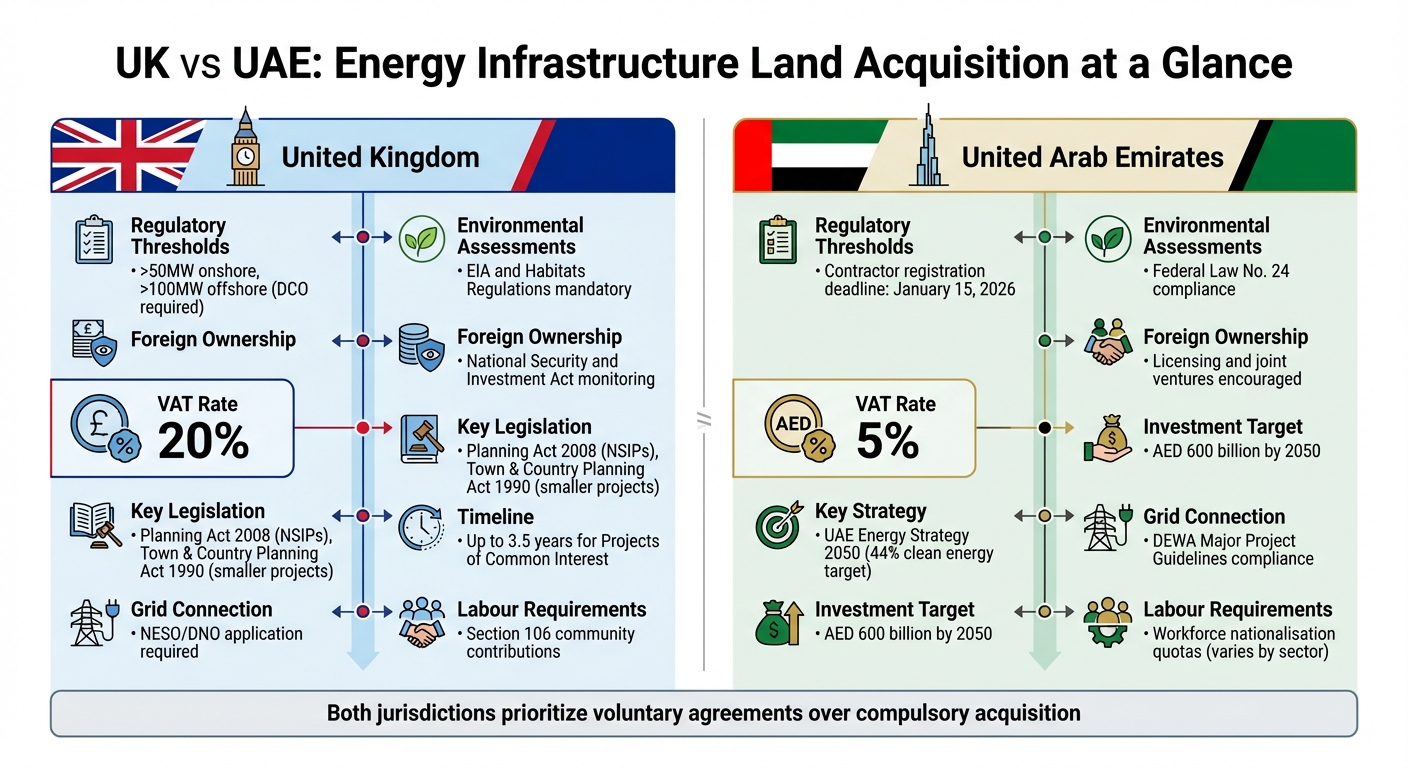

Acquiring land for energy projects in the UAE and UK is a complex process involving legal frameworks, environmental regulations, and stakeholder negotiations. Here’s a quick breakdown of the key steps:

- Legal Pathways: In the UK, project size determines the regulatory process. Large projects (over 50MW onshore or 100MW offshore) require a Development Consent Order (DCO) under the Planning Act 2008. Smaller projects fall under local planning authorities.

- Environmental Assessments: Mandatory evaluations include Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) and Habitats Regulations to identify protected species and habitats.

- Ownership Verification: Confirm land ownership through title searches, site visits, and local records. For unregistered land, additional investigation is required.

- Foreign Ownership Rules: The UK monitors investments under the National Security and Investment Act, while the UAE enforces contractor registration and licensing deadlines.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Early negotiations with landowners, tenants, and other parties can prevent delays. Compulsory purchase is considered a last resort.

- Financial Planning: Budget for costs like registration fees, grid connection expenses, and compensation payments. VAT rates differ - 20% in the UK and 5% in the UAE.

Quick Comparison

| Aspect | UK | UAE |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Thresholds | >50MW onshore, >100MW offshore (DCO required) | Contractor registration by Jan 2026 |

| Environmental Assessments | EIA and Habitats Regulations | Federal Law No. 24 compliance |

| Foreign Ownership Rules | National Security and Investment Act | Licensing and joint ventures encouraged |

| VAT | 20% | 5% |

Understanding these steps upfront ensures smoother project execution and reduces risks. Keep reading for detailed guidance tailored to both regions.

UK vs UAE Energy Infrastructure Land Acquisition: Regulatory Requirements and Key Differences

Pre-Acquisition Due Diligence

Ownership Verification

Start by performing register searches to confirm ownership and identify any legal claims. In England and Wales, you can use HM Land Registry's MapSearch, a free online tool, to check if a property is registered and obtain its title numbers. For results with indemnity protection, request a Search of the Index Map, as outlined in Practice Guide 10.

To dig deeper, use Form OC1 to obtain an official copy of the title, which confirms ownership and highlights any encumbrances. If you need to check for updates since a specific date, submit Form OS3 for a search without priority.

For unregistered land, ownership must be verified by examining title deeds and any related cautions. On-the-ground efforts like site visits and local enquiries are crucial, as some interests - such as rights of access or servitudes - might not appear in property records.

If the ownership is unclear or the owner is unknown, explore Council Tax records, electoral rolls, and the Register of Companies. You can also reach out to previous title solicitors, utility providers, or even Royal Mail. As a last resort, consider issuing fix notices or public advertisements. In cases where owners refuse to disclose information, applicants for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects can request a "land interests notice" under Section 52 of the Planning Act 2008 to compel disclosure.

These steps ensure clear title verification before moving on to assess foreign ownership and site-specific conditions.

Foreign Ownership Restrictions

Once ownership is confirmed, check for restrictions on cross-border acquisitions. Foreign investments in UK energy infrastructure are closely monitored under the National Security and Investment Act. The government may impose conditions to safeguard sensitive areas, especially near military sites. For instance, in March 2025, the UK government approved the acquisition of British infrastructure company Transmission Investment by TAQA Transmission, a subsidiary of the state-owned Abu Dhabi National Energy Company. The approval came with conditions designed to secure electricity connections near a nuclear submarine base in Scotland.

In the UAE, regulations require all contractors operating in Dubai - including those in free zones and special development zones - to be registered and hold a valid commercial licence by 15 January 2026. While certain infrastructure and airport-related construction projects are temporarily exempt from some regulations, registration is mandatory within one year. Non-compliance can result in fines ranging from AED 1,000 to AED 100,000, escalating to AED 2,000,000 for repeat violations within a year.

For large infrastructure projects in the UAE, consider forming joint ventures between local and international contractors. These joint ventures can be structured as either incorporated (limited liability) or unincorporated (joint and several liability) entities. Ensure any international contractors or partners are registered with the Dubai Municipality by the January 2026 deadline to avoid licence revocation or hefty fines.

Preliminary Site Assessment

After verifying ownership and compliance with regulations, conduct a thorough site assessment. Survey the land to identify protected species and habitats. This step is crucial to meet the requirements of the Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 and Habitats Regulations. According to the Planning Inspectorate:

"The applicant may need to enter land... to: carry out surveys to understand the natural habitat and to identify any protected species; take measurements and levels; drill bore holes and take samples to understand the nature of the subsoil".

If access for surveys is denied by the landowner, you can invoke the "right to enter land" under Section 53 of the Planning Act 2008. This right typically expires 12 months after authorisation or upon the submission of the infrastructure application. Ensure you provide at least 14 days' notice to any occupiers before exercising this right.

Evaluate grid connection feasibility, determine if overhead lines or wayleaves are required, and check for restrictive covenants. For sites near high-voltage lines (132kV and above), compliance with ICNIRP guidelines on public exposure to electromagnetic fields is essential. Ensure that the site assessment aligns with the criteria outlined in the relevant National Policy Statements used by the Planning Inspectorate during project evaluations.

CHECKLIST FOR SOLAR LAND ACQUISITION

Regulatory Compliance and Licensing

This section breaks down the key regulatory approvals and licensing steps required after completing due diligence.

Zoning and Land Use Permissions

In the UK, the project capacity determines which consenting regime applies. For onshore projects exceeding 50MW or offshore projects over 100MW, these are classified as Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) and require a Development Consent Order (DCO) under the Planning Act 2008. Smaller onshore projects (50MW or less) fall under the jurisdiction of local planning authorities, governed by the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. Onshore wind farms in England and Wales, regardless of their size, always require local authority approval. Offshore generating stations, ranging from 1MW to 100MW, are managed by the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989.

Here’s a quick overview of how different UK project types are regulated:

| Project Type (UK) | Capacity/Threshold | Primary Legislation | Decision Maker |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onshore Power Station | > 50MW | Planning Act 2008 | Secretary of State (via Planning Inspectorate) |

| Onshore Power Station | ≤ 50MW | Town & Country Planning Act 1990 | Local Planning Authority |

| Onshore Wind Farm | Any size | Town & Country Planning Act 1990 | Local Planning Authority |

| Offshore Power Station | > 100MW | Planning Act 2008 | Secretary of State (via Planning Inspectorate) |

| Offshore Power Station | 1MW to 100MW | Electricity Act 1989 (Section 36) | Marine Management Organisation (MMO) |

| Overhead Lines | < 132kV | Electricity Act 1989 (Section 37) | Secretary of State (BEIS/DESNZ) |

In the UAE, energy infrastructure development aligns with the UAE Energy Strategy 2050. This strategy sets ambitious goals, including a diversified energy mix of 44% clean energy, 38% gas, 12% clean coal, and 6% nuclear energy. It also involves an investment of AED 600 billion by 2050 while aiming to reduce carbon emissions from power generation by 70%.

Once zoning permissions are granted, ensure environmental assessments meet both local and UK-specific regulatory standards.

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA)

Energy projects in the UK must adhere to EIA regulations tailored to the type of project. For developments under the 1990 Town and Country Planning Act, the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 apply. For power stations, the Electricity Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017 (No. 580) are relevant. When it comes to NSIPs, the Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 define the environmental review process required before granting a DCO.

In the UAE, EIA processes are mandated under Federal Law No. 24. Developers must secure environmental clearance from the Ministry of Climate Change and Environment before moving forward with land acquisition or construction.

Once zoning and EIA approvals are secured, focus shifts to obtaining sector-specific licences.

Sector-Specific Licences

For NSIP projects in the UK, the DCO process involves several stages: pre-application stakeholder consultations, a 28-day acceptance phase, a pre-examination period for stakeholder feedback, up to six months for examination, and a final decision within three months. For Projects of Common Interest (PCIs), the permitting process is capped at 3.5 years - two years for pre-application and 1.5 years for determination.

Large power stations (300MW or more) must ensure space is available for future carbon capture and storage equipment. Offshore renewable energy developers are also required to submit a decommissioning programme under the UK Energy Act 2004, which may include financial security provisions.

In the UAE, renewable energy projects require approvals from the Emirates Water and Electricity Company (EWEC) or the relevant emirate-level authority. The UAE Energy Strategy 2050 aims to increase clean energy contributions to 50% while improving energy efficiency by 40%, potentially saving AED 700 billion.

Checklist summary: Zoning permissions secured, EIA compliance confirmed, licences obtained.

Environmental and ESG Requirements

Once regulatory approvals are in place, it's crucial to assess environmental risks and incorporate ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) principles into your land acquisition strategy. Both the UK and UAE have introduced stricter sustainability rules, making this step vital for ensuring project success.

Environmental Risk Evaluation

Start by conducting an environmental risk assessment that examines biodiversity, water resources, soil quality, and climate-related hazards. In the UK, this involves evaluating potential impacts on protected areas such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), National Nature Reserves, National Parks, and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

For land previously used for industrial purposes, check for soil contamination from activities like railway operations or hazardous material storage. Offshore and coastal projects bring additional challenges, such as coastal erosion, rising sea levels, and seabed impacts, which fall under the jurisdiction of The Crown Estate. Technology-specific risks also need attention; for instance, solar PV systems must withstand high temperatures and flooding in low-lying regions. Don't overlook transport and operational risks that are unique to the type of technology deployed.

In the UAE, align environmental risk evaluations with ENMI standards and prepare for mandatory ESG reporting, set to begin in 2025. Consult statutory bodies for environmental guidance during the early stages of project planning. Meanwhile, in the UK, organisations like Natural England, the Environment Agency, or the Marine Management Organisation can provide preliminary advice, often within 21 days of a request.

These evaluations form the backbone for integrating effective ESG reporting and carbon reduction initiatives into the project plan.

ESG Reporting and Carbon Reduction

In the UK, renewable electricity generation projects - whether onshore or offshore - are classified as Critical National Priority (CNP) infrastructure, reflecting their importance to achieving net-zero goals. This designation allows renewable projects to proceed even if they pose significant challenges to protected areas, provided the mitigation hierarchy is followed: avoid, reduce, mitigate, and compensate.

"Electricity generation from renewable sources is an essential element of the transition to Clean Power 2030 Mission, net zero and meeting our statutory targets for the sixth carbon budget (CB6)." – National Policy Statement for renewable energy infrastructure (EN-3), 2025

Your Environmental Statement should address the project's long-term resilience to climate risks such as flooding, storm surges, and drought. With UK electricity demand potentially more than doubling by 2050 - requiring a fourfold increase in low-carbon energy generation - it's critical to integrate ambitious carbon reduction targets into your land acquisition strategy. Similarly, in the UAE, mandatory ESG reporting starting in 2025 will require developers to align projects with the UAE Energy Strategy 2050's carbon reduction objectives from the outset.

Once carbon reduction goals are set, the next step is to develop effective habitat mitigation strategies.

Habitat Mitigation Planning

Habitat mitigation must follow a clear hierarchy during site selection and pre-application phases. Begin by avoiding sensitive areas entirely. If that's not possible, reduce environmental impacts by adjusting project layouts or incorporating nature-friendly designs. Mitigation measures - such as installing green roofs, bird boxes, and living walls - should come next. Finally, when necessary, compensate by creating new habitats elsewhere.

For offshore wind projects, adherence to the upcoming Offshore Wind Environmental Standards (OWES) is essential. Collaborate with The Crown Estate and the Marine Management Organisation to manage seabed impacts. Establish ecological baselines by conducting seasonal surveys with qualified ecologists to identify key species and habitats before starting development. Additionally, good design principles for renewable energy projects should explore opportunities for co-existence or co-location with other marine or land uses, minimising the overall environmental footprint.

If your project requires both planning permission and environmental permits, consider "twin-tracking" your applications. This approach can streamline the process and reduce repetitive information requests. Finally, consult Natural England's "standing advice" on protected species to understand how local planning authorities will evaluate habitat-related applications.

sbb-itb-0a9f22b

Stakeholder Engagement and Risk Management

Securing land for energy infrastructure involves navigating a maze of stakeholder dynamics. Both the UK and UAE have unique frameworks for engaging communities, addressing labour requirements, and preparing for potential delays.

Community and Utility Consultations

In the UK, developers must conduct detailed stakeholder checks to identify all individuals or organisations with legal interests in the land. This includes owners, tenants, lessees, and mortgage holders. To gather this information, land referencing questionnaires are distributed. If stakeholders refuse to comply, developers can issue a land interests notice under Section 52 of the Planning Act 2008, making non-compliance a criminal offence.

Stakeholders are typically grouped into categories: Host Local Authorities (where the land is located), Statutory Parties (such as the Environment Agency), Parish Councils, and Affected Persons whose land is subject to acquisition. Before submitting an application for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs), developers must publish a programme document detailing how and when public and stakeholder engagement will occur. Once requested, the Planning Inspectorate generally takes about three months to issue a land interests notice.

"Compulsory purchase is intended as a last resort and acquiring authorities are expected to try to acquire land by agreement before resorting to compulsory purchase." – GOV.UK

In the UAE, the focus of stakeholder engagement is primarily on government entities and local commercial agents. Early discussions with distribution companies and relevant ministries are critical, especially for projects involving utility connections. Developers should document all communications - including letters, emails, and meeting notes - as this evidence may be required in case of disputes or challenges to authorisations. These steps help align community and utility interests with project timelines.

Labour and Planning Obligations

Labour compliance varies significantly between the UK and UAE. In the UK, Section 106 agreements under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 often require developers to make voluntary contributions or enter into contractual commitments. These commitments could involve funding local infrastructure, community facilities, or environmental improvements to secure project approval from local authorities.

In the UAE and the broader GCC region, workforce nationalisation policies are a central requirement. For example, Qatar’s Qatarisation legislation, introduced in December 2023, sets phased quotas for private sector employers to fulfil between 2025 and 2027. Oman aims for a 30% nationalisation rate by 2040, with over 30 professions - particularly in IT and engineering - reserved exclusively for Omani nationals. From 1 April 2025, foreign-owned companies in Oman must employ at least one Omani national within their first year of operation.

Failure to comply with these policies can result in severe penalties. In Bahrain, non-compliance may lead to business suspension, electronic "flags" during registration renewal, and fines ranging from BHD 1,000 to BHD 4,000 (approximately AED 9,750 to AED 39,000). For digital banking projects in Oman, Omanisation requirements start at 50% in the first year and increase by 10% annually, reaching 90% by the fifth year. Meeting these labour obligations is critical to maintaining project momentum and avoiding regulatory setbacks.

Contingency Planning

Land acquisition frequently encounters challenges, making contingency planning essential. Using phased acquisition approaches, such as "Option and Lease" agreements, can help manage risks. This method provides time to secure planning consents, complete due diligence, and obtain grid connection offers before committing significant capital.

For UK projects subject to the National Security and Investment (NSI) Act, developers must provide evidence like 13-week cash flow statements and auditor analyses if the target company is in financial distress. This documentation can accelerate the national security assessment process with the Investment Security Unit. The NSIP process itself typically spans about 17 months from application submission to a final decision.

Allow time for objections and public inquiries. In the UK, after a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) is issued, stakeholders have a minimum of 21 days to file formal objections. If a public inquiry is needed, it is usually scheduled within 22 weeks of the relevant date. Developers can often negotiate formal undertakings with affected parties, agreeing on limitations to how powers are exercised in exchange for withdrawing objections.

In Oman, leveraging streamlined licensing systems in Special Economic Zones under Royal Decree 38/2025 can help minimise administrative delays. After acquiring land, conducting "asset onboarding" reviews is crucial. These reviews identify gaps in due diligence data and incorporate findings into property management strategies, ensuring smoother project execution.

Financial and Operational Checklist

After addressing regulatory compliance and engaging with stakeholders, it's crucial to establish solid financial and operational frameworks. When budgeting for energy infrastructure or land acquisition, consider regional costs and timelines. For instance, VAT rates differ significantly between regions: the UK applies a 20% VAT, while the UAE's VAT is only 5%. This disparity can have a substantial effect on the overall project costs, especially for large-scale renewable energy projects or data centre investments.

UK-Specific Considerations

In the UK, developers need to account for several upfront and ongoing costs. These include option fees to secure land rights for 18 months, with possible extension fees for an additional 12 months. Once secured, developers typically make one-off easement payments, followed by periodic lease rents for long-term access. Grid connection expenses are another major factor, covering application fees to the National Energy System Operator (NESO) or Distribution Network Operators (DNO), along with potential "tolling fees" for network charges and imbalance payments.

Other key costs include Reinstatement Bonds - financial deposits to cover land restoration at the end of a project - and compensation for environmental impacts caused by construction.

UAE and GCC Considerations

Projects in the UAE and GCC regions face different financial requirements. Licensing costs are streamlined through centralised platforms like Sijilat or one-stop-shop systems. Additionally, compliance with workforce nationalisation quotas - often set at 20% in specific sectors - adds to operational costs. In Dubai, grid connectivity must align with DEWA's Major Project Guidelines – Electricity, which were last updated in July 2025.

Cost Breakdown and Budgeting

| Cost Component | United Kingdom | United Arab Emirates |

|---|---|---|

| VAT | 20% | 5% |

| Option Fee | Initial payment for 18 months, plus extension fees | Not applicable (direct licensing approach) |

| Easement Payment | One-off payment upon Deed of Grant | Varies by zone and project type |

| Survey Licence Fee | Required for ground investigations | Included in NOC applications |

| Reinstatement Bond | Mandatory for site restoration | Standard decommissioning obligations |

| s.106 Payments | Community/infrastructure contributions | Not applicable |

| Grid Application | NESO/DNO fees + supervision costs | DEWA Major Project fees |

UK Grid Connection Feasibility

In the UK, developers must submit a technically sound connection application to either the National Grid or a DNO to secure a clock start date. The process involves multiple steps:

- Option Agreement: A typical 18-month period for site investigations.

- Deed of Grant: Issued after planning permissions and technical reviews are completed.

- Easement Implementation: Construction usually begins within 12 weeks of granting easement rights.

Substation lands require interface agreements, while non-substation lands follow prescribed easement strips. Developers should also be aware that National Grid requires two months' notice to schedule engineers for supervision, and construction information must be submitted 10 weeks in advance to meet technical and environmental standards. Recent UK Contracts for Difference (CfD) auctions set solar project pricing at £45.99/MWh, offering a benchmark for revenue planning.

Dubai Grid Connection Feasibility

In Dubai, DEWA's Major Project Guidelines outline grid connectivity and infrastructure requirements. Early engagement with distribution companies and relevant ministries is critical, as is maintaining thorough documentation of communications. This helps in resolving disputes or navigating authorisation challenges.

Legal Review and Contract Finalisation

Beyond budgeting, a thorough legal review is essential to safeguard your investment. In the UK, developers typically use 18-month option periods to conduct site investigations and secure necessary permissions before committing to full easement payments. A signed Connection Agreement with NESO or a DNO is often required before land rights are fully granted.

Contracts must clearly define environmental liabilities, ensuring that developers are not held accountable for historic contamination.

"The developer is not responsible for historic contamination. However, it is responsible for any contamination it causes or exacerbates." – National Grid Electricity Transmission

National Grid will reject planning applications that impose unacceptable conditions, such as binding their retained land or requiring land donations without indemnity. For projects involving compulsory purchase, General Vesting Declarations under the Compulsory Purchase Act 1981 must be registered with HM Land Registry, with fees starting at £40 if compensation remains unsettled.

In the UAE and GCC, legal reviews often focus on foreign ownership restrictions. While the UAE and Bahrain permit 100% foreign ownership in many sectors, industries like banking and insurance require special approvals. Additionally, projects subject to the UK's National Security and Investment Act may face additional legal filing expenses. For UK energy projects, standard easement terms typically last 30 to 40 years, necessitating effective long-term contract management.

Post-Acquisition Validation

Once the land acquisition process is complete, the focus shifts to securing legal ownership and ensuring compliance with relevant regulations. This involves registering the title and keeping a close eye on compliance requirements to avoid delays or legal complications.

Title Registration and Permit Approvals

In the UK, ownership registration must be completed with HM Land Registry once a general vesting declaration is in effect. For registered land, submit Form AP1 along with a certified general vesting declaration and confirmation certificate. For unregistered land, use Form FR1 instead.

The registration fees are calculated under Scale 2 of the Land Registration Fee Order, based on the land's value. If compensation hasn’t been fully settled, a minimum payment of £40 is required, accompanied by a commitment to pay the remaining balance later. For large-scale energy projects involving multiple parcels of land, you can request a "development scheme" from HM Land Registry. This allows separate acquisitions to be combined into a single registered title as they are acquired, avoiding the hassle of merging them later.

It’s also important to account for easements and restrictive covenants, as they are not automatically extinguished by the acquisition unless explicitly stated by law. Make sure these are properly documented, as outlined in earlier stages.

This process finalises the formal transfer of ownership and lays the groundwork for ongoing compliance efforts.

Continuous ESG and Compliance Audits

Once title registration is confirmed, attention should shift to maintaining Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards and regulatory compliance. In the GCC, regulations are becoming stricter. For example, ESG reporting became mandatory in Oman and Bahrain in 2025, while Qatar continues to offer voluntary guidelines with a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 25% by 2030. Bahrain has also committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2060.

To meet these expectations, consider adopting Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards and align your compliance efforts with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. For projects located in Oman's Special Economic Zones, take advantage of the one-stop-shop system introduced under Royal Decree 38/2025 to simplify post-acquisition licensing.

Another critical area is workforce nationalisation compliance. In Oman, foreign-owned companies are required to employ and register at least one Omani national with the Social Protection Fund within their first year of operation. The requirements are even stricter for digital banks, which must achieve 50% localisation in their first year, increasing to 90% by year five. Non-compliance can result in hefty fines - in Bahrain, these range from BHD 1,000 to BHD 4,000 (approximately AED 9,700 to AED 38,900), and could even lead to business suspension.

In the UK, developers handling Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) must continue investigating land interests even after submitting their applications to fulfil legal notification obligations. If information about land interests is withheld, developers may apply for authorisation under Section 52 of the Planning Act 2008 to issue a formal land interests notice. However, these authorisations are time-sensitive, typically expiring 12 months after being granted, so it’s crucial to act promptly.

Conclusion

Acquiring land for energy infrastructure is a process that demands careful planning and precision. Success hinges on four key elements: conducting thorough due diligence to identify all stakeholders with legal interests in the land, strictly following regulatory frameworks like the National Policy Statements (effective from 6 January 2026), engaging meaningfully with stakeholders before considering statutory powers, and ensuring detailed financial planning to account for all associated costs, including fees, claims, and compliance expenses.

"Compulsory purchase is intended as a last resort and acquiring authorities are expected to try to acquire land by agreement before resorting to compulsory purchase." – Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

Timelines for such projects vary significantly - ranging from three months for rights of entry under Section 53 of the Planning Act 2008 to as long as 3.5 years for permitting Projects of Common Interest. This variability highlights the need for early-stage planning and meticulous record-keeping. Keeping detailed records of all communications and expenditures is essential, especially when supporting compensation claims or proving reasonable efforts to negotiate voluntarily.

Financial considerations go beyond the initial cost of acquiring land. Fees for registration with HM Land Registry depend on the land's value and follow either Scale 1 or Scale 2 guidelines.

The principle of equivalence ensures that landowners are compensated fairly. By involving experienced property advisers from the outset, maintaining comprehensive documentation, and prioritising voluntary agreements over statutory measures, developers can navigate the complexities of land acquisition. This approach reduces risks and paves the way for successful projects, whether in the UAE or the UK.

FAQs

How does the land acquisition process for energy projects differ between the UK and the UAE?

The processes for land acquisition in energy projects reveal striking contrasts between the UK and the UAE, shaped by their unique regulatory and administrative systems.

In the UK, land acquisition follows a structured framework laid out by legislation like the Planning Act 2008. For large-scale projects deemed nationally significant, developers are required to obtain a Development Consent Order (DCO). This order consolidates various permissions into a single approval, but the journey to secure it is far from simple. It involves detailed environmental assessments, mandatory public consultations, and procedures for compulsory acquisition. Essentially, it’s a multi-stage process with rigorous checks, ensuring that all stakeholders are considered.

On the other hand, the UAE takes a more centralised approach. The Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure plays a key role, acting as the main authority for land-related matters. The process is streamlined, with government-led initiatives offering unified services through dedicated programmes. While the procedural specifics aren’t as openly detailed as in the UK, the focus is on efficiency and direct oversight, avoiding the complexity of involving multiple agencies.

In essence, the UK employs a detailed, legislation-driven system prioritising public input and scrutiny, whereas the UAE opts for a centralised, government-coordinated model that prioritises speed and simplicity.

How can developers ensure they meet environmental and ESG regulations in the UK and UAE?

Developers aiming to meet environmental and ESG regulations need to align with region-specific guidelines and adopt recognised best practices.

In the UK, projects identified as Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects may require a Development Consent Order (DCO). A thorough Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is also essential, following the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017. Early collaboration with organisations like Natural England and other relevant bodies can help address concerns related to habitat protection, flood risks, and climate resilience. Additionally, incorporating frameworks such as the UK Corporate Governance Code and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) into project documentation is vital for ESG compliance.

In the UAE, developers must adhere to the Environmental Clearance (EC) framework, which mandates an EIA for specified projects. This process, overseen by the Dubai Municipality, requires detailed reporting that aligns with the Dubai Strategic Vision and local benchmarks for air quality, water usage, and biodiversity. Adopting globally recognised standards like ISO 14001 and including metrics such as greenhouse gas emissions and social impact in project plans is equally important. Regular engagement with stakeholders and transparent ESG reporting play a critical role in ensuring compliance and securing project approvals in both regions.

What financial costs, including VAT, should be considered for energy projects in the UK and UAE?

When working on energy projects in the UK or UAE, it's crucial to factor in financial considerations like Value-Added Tax (VAT) and other regulatory fees. These costs vary significantly between the two regions, and they can have a notable impact on your project's overall budget.

To ensure precise cost planning, you should consult the Federal Tax Authority (FTA) in the UAE or HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) in the UK. It’s also a good idea to seek guidance from tax and financial professionals. They can help you navigate region-specific taxes and fees, including those tied to land acquisition and energy infrastructure development, ensuring compliance and a clear understanding of all fiscal obligations.